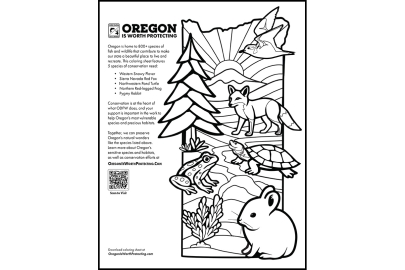

The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) protects the state's fish and wildlife species, and their habitats. We do this through science-based management. Our mission is to protect and enhance Oregon's fish and wildlife, and the habitats they use, for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. Conservation is at the heart of what we do, and your support is important in the work to help Oregon's species and habitats thrive.

Featured here are some of Oregon's species of greatest conservation need. These are native species that are imperiled and in need of attention. Conservation efforts today can help prevent these species from disappearing from Oregon. Some of the risks to these animal populations include pollution, climate change, invasive species, and barriers to animal movements. Taking action is key to maintaining Oregon's extraordinary biodiversity.

Learn more about each of these unique species and some of the threats they face below.

Learn about the State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP)

Western snowy plover

- The western snowy plover is a small shorebird that is a resident of sandy beaches, salt ponds, and alkaline lakes. These small sand-colored birds often go unnoticed as they feed along sandy beaches or lakeshores.

- Oregon's coastal dunes are the largest coastal dunes in North America with some dunes reaching 500 ft above sea level and are home to the western snowy plover.

- Western snowy plovers are tiny birds that are smaller in size than a robin. Snowy plover chicks are so small that they are roughly the size of a human's thumb when they hatch, looking like tiny fluffy marshmallows on toothpicks.

- Oregon has two breeding populations of western snowy plover: the threatened population that breeds in coastal dunes, and the interior population, which can be found nesting south central Oregon in places like Summer Lake or Lake Abert.

- The coastal population of western snowy plover is listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act, and there are around 500 birds remaining in coastal Oregon.

- Western snowy plovers make their nests directly in the sand, where their eggs are well camouflaged and protected from predators. This often makes them barely visible to even a well-trained eye.

- Western snowy plovers are an indicator species for the coastal dune ecosystem. An indicator species is a plant or animal group that provides information about the health and condition of an ecosystem through their population's presence, size and abundance.

- The western snowy plover is a species of greatest conservation need in Oregon, and proactive conservation efforts can help prevent their populations from declining further. Western snowy plover populations are threatened by factors including habitat loss, the introduction of invasive beachgrass, human disturbance, and climate change.

Sierra Nevada red fox

- The Sierra Nevada red fox is a montane (high elevation mountain-living) subspecies of red fox that is adapted to cold, snowy environments.

- The Sierra Nevada red fox has different physical traits (adaptations) than other foxes to make it capable of living at higher elevations. For example, they have furrier paws that act like snowshoes, have a thick coat to keep them warm, and are smaller-bodied than other subspecies which makes it easier for the Sierra Nevada red fox to walk on top of snow to navigate and find food in winter.

- Sierra Nevada red foxes are limited to high elevation habitat along the crest of the Cascades. This explains why sightings of the Sierra Nevada red fox are most reported to us when people are out recreating (i.e., skiing, backpacking, hiking). We receive a lot of sightings at ski resorts and locations like Mt. Hood Meadows, Hoodoo Ski Area, Timberline, and Mt. Bachelor. Sierra Nevada red fox are also known to live in Crater Lake National Park.

- Although their name says ‘red fox' they come in a variety of color variations (known as morphs) – traditional red, black/silver, and a mix of red with dark brown or black markings called a "cross phase." Sierra Nevada red fox in Oregon are often black and silver, looking almost wolf-like in appearance.

- One of the biggest threats Sierra Nevada red fox face is climate change. Decreasing snowpack makes it easier for other animals to enter the areas that were normally only accessible to Sierra Nevada red fox, forcing them to compete for food sources and often becoming meals for other predators.

- The southern Cascades population of Sierra Nevada red fox has been petitioned for listing under the federal Endangered Species Act.

- The Sierra Nevada red fox is a species of greatest conservation need in Oregon, and proactive conservation efforts can help prevent their populations from declining further. Threats to the species in Oregon include climate change, habitat loss and fragmentation, increasing wildfire severity and frequency, and increased vulnerability to impacts due to their small population size.

Northern red-legged frog

- The northern red-legged frog is a medium size frog with bright red legs found in a variety of aquatic habitats in western Oregon.

- Growing up to four inches in length (not including the legs) northern red-legged frogs are the largest frog species native to Oregon. American bullfrogs are larger (growing up to eight inches!) but are not native to Oregon. On average, female northern red-legged frogs are about 4 inches in length, which is the same as the average width of a person's hand. Males are smaller than females, averaging only about 2-2.5 inches in length.

- Northern red-legged frogs can travel up to 3 miles between their summer and winter habitats. That's quite a feat for a frog that's only a few inches long!

- Northern red-legged frogs can live more than 10 years. Limited information describing the species is available, and more research is needed to better understand their average lifespan as well as other basic life history traits.

- When mating, northern red-legged frogs exclusively make their mating calls or vocalizations underwater to attract their mating partner.

- Red-legged frogs breed in the winter. Their biggest breeding season occurs January - March. The breeding season is a dangerous time for northern red-legged frogs as they often must cross roads to get to their breeding ponds. In some areas around Portland where northern red-legged frogs are still found, volunteers work to help shuttle breeding frogs on their way to and from breeding ponds to help them cross dangerous busy highways and railroad tracks.

- Get involved and learn more about the Harborton Frog Shuttle.

- Completed in 2024, Palensky Wildlife Crossing is the first of its kind in the state, specifically built as an amphibian underpass for northern red-legged frogs to combat some of the threats they face traveling across the landscape.

- Northern red-legged frogs are visual hunters. Once they locate prey, they use their large, sticky tongue to capture a wide variety of invertebrates (an animal without a backbone). Large adults may eat smaller frogs or salamanders, while the tadpoles feed on algae.

- Northern red-legged frogs are impacted by many factors including climate change's impact on their ecosystems, increased pollution in the environment, invasive species like bullfrogs that prey upon adult red-legged frogs, their tadpoles, and their eggs, and lack of safe passage to and from their breeding areas.

- The northern red-legged frog is species of greatest conservation need in Oregon, and proactive conservation efforts can help prevent their populations from declining further.

Pygmy rabbit

- The pygmy rabbit is the smallest species of rabbit in North America and lives in sagebrush habitats in eastern Oregon.

- Weighing in at only 12 ounces fully grown, pygmy rabbits are tiny animals - they are roughly the size of a mango or a can of soda.

- An easy way to distinguish a pygmy rabbit from a cottontail rabbit (that is a very common species to encounter) is that pygmy rabbits do not have white on their tail. Their small size, short ears, and small hind legs are also distinguishing features.

- Pygmy rabbits are the only North American rabbit that dig their own burrows. These complex burrow structures can have as many as 15 different openings. They use burrows to give birth and nurse their babies, warm up during winter, cool down during hot summer temperatures, and hide from predators. They can also dig burrows in the snow (some of the areas where they live get a lot of snow).

- Pygmy rabbits have a lifespan of 1-3 years.

- Pygmy rabbits only breed in the springtime.

- Sagebrush makes up almost the entire diet for pygmy rabbits in winter months. They are a sagebrush obligate, which means they require sagebrush to survive.

- Pygmy rabbits are known to climb sagebrush, especially when foraging for food. They are one of the only rabbit species that can do this. They will climb sagebrush to reach and eat its green leaves.

- The pygmy rabbit is a species of greatest conservation need in Oregon, and proactive conservation efforts can help prevent their populations from declining further. Pygmy rabbits face many threats, including habitat loss and fragmentation, development, invasive species, disease, and wildfire. Their specific habitat requirements, including sagebrush and the soil conditions that allow them to burrow, limit where they can live.

Northwestern pond turtle

- The northwestern pond turtle is one of Oregon's two native turtle species and is closely associated with aquatic habitats.

- The oldest living northwestern pond turtle known is more than 60 years old. We don't know how old they can truly live, but there are long term studies that are underway to help biologists better understand their lifespans.

- Northwestern pond turtles have unique markings on the top (carapace) and bottom (plastron) of their shell that can be used like a fingerprint. Biologists can identify individual turtles by these unique patterns.

- Northwestern pond turtles are known from both sides of the Cascades, though they are primarily found west of the Cascade Mountains in Oregon, with the largest populations in the drainages of the Willamette, Umpqua, Rogue, and Klamath Rivers.

- Some northwestern pond turtles spend months underwater hibernating over winter. When they hibernate like this, they are capable of not eating or coming up to breathe air for months. They can survive long periods of time underwater by absorbing the oxygen that they need through their skin.

- Turtles need to be in the water to swallow their food.

- As hatchlings, northwestern pond turtles are only about the size of a silver dollar. Their small size makes them vulnerable to being eaten by non-native predators like bullfrogs.

- The northwestern pond turtle is a species of greatest conservation need in Oregon, and proactive conservation efforts can help prevent their populations from declining further. Northwestern pond turtles are negatively impacted by threats including the illegal pet trade and trafficking, invasive species (i.e., bullfrogs, red-eared slider turtles, snapping turtles), and habitat loss and degradation.

- The northwestern pond turtle is proposed threatened by the federal government under the federal Endangered Species Act.

Townsend's big-eared bat

- The Townsend's big eared bat is one of Oregon's 15 native bat species, a social species that is most recognizable by their long ears.

- Townsend's big-eared bat can be identified by their big, long ears that are joined at the base and a short snout with two large, fleshy glands on each side. The color of their fur is highly variable and can range from pale cinnamon brown to slate gray to dark brown.

- Adults are 3 to 4.5 inches in length, with a wingspan of 12 inches. They weigh 5 to 13 grams.

- The average lifespan is 4 to 10 years. The oldest known Townsend's big-eared bat lived to be over 21 years old!

- Females give birth to a single pup (baby bat), usually in June to July. Pups are born with closed eyes and no fur, though they develop quickly. The pups can fly after only three weeks and may continue nursing for up to two months. Each pup makes a unique call that its mother recognizes.

- Townsend's big-eared bats are nimble when flying and use their enormous ears to detect prey and help navigate using echolocation. They have large wings in comparison to their body size, allowing them to skillfully maneuver through the air, even hovering during flight!

- They hibernate in large, open areas in mines, caves, and protected areas. While hibernating or roosting, they curl their ears down and back, giving them the characteristic look of ram's horns.

- Townsend's big-eared bats are insectivores (they eat insects) and are moth specialists - they eat mostly moths! They are effective at helping to control moth populations and can help limit environmental and agricultural damage from insects.

- Townsend's big-eared bat is a species of greatest conservation need in Oregon, and proactive conservation efforts can help prevent their populations from declining further. Threats impacting the populations of Townsend's big-eared bat in Oregon include human disturbance, declining populations of insect prey, and vandalism at caves and other roost sites.

Oregon slender salamander

- The Oregon slender salamander is a small terrestrial salamander species found on the west slope of the Oregon Cascades. At first glance, they can be described as worm-like in appearance. They are deep brown to black in color overall, have a long, thin body, and a long tail.

- The Oregon slender salamander is endemic to (only found in) Oregon.

- The number of toes on their hind foot (four) and the characteristic large blueish-white blotches on their sides and belly differentiate Oregon slender salamanders from all other salamander species in Oregon.

- The Oregon slender salamander is small and doesn't move far during its lifetime. Adults average 3.5 to 4.5 inches in length from nose to tail.

- Oregon slender salamanders may be found in younger moist forests where large logs and downed woody debris is available. They typically are found in forested areas, but some individuals have been found in suburban landscapes around Portland.

- They have long tails, which can be 1 to 1.75 times their body length! Individuals are often found with broken or missing tails. It is possible that they lose their tails in order to escape predation. When disturbed, Oregon slender salamanders may coil and uncoil their body rapidly to flip, launching their body dramatically. This behavior is thought to help prevent predation.

- For many years, Oregon slender salamanders were thought only to occur in mature forests in the Cascades. Recently, small remnant populations have been located in suburban areas, even in Forest Park in Portland! Since individual Oregon slender salamanders do not disperse far, it is thought that these remnant populations may have persisted in these small pockets of suitable habitat as the city and suburban areas developed around them.

- The Oregon slender salamander is a species of greatest conservation need in Oregon, and proactive conservation efforts can help prevent their populations from declining further. This salamander is one of the least studied species in the Pacific Northwest, and their life history is poorly described. Learning more about this unique Oregon species can help ensure it is protected.